Elizabeth Bayleigh once argued as a barrister before Britain’s highest judges without flinching. Yet when a specialist told her a brain scan was “entirely normal,” she nodded, speechless, despite an instinct that something was terribly wrong. Years later that missed aneurysm ruptured, leaving her paralysed and blind; only anger and determination finally pushed her to demand a second opinion that discovered a second aneurysm and that saved her from a second life threatening event.

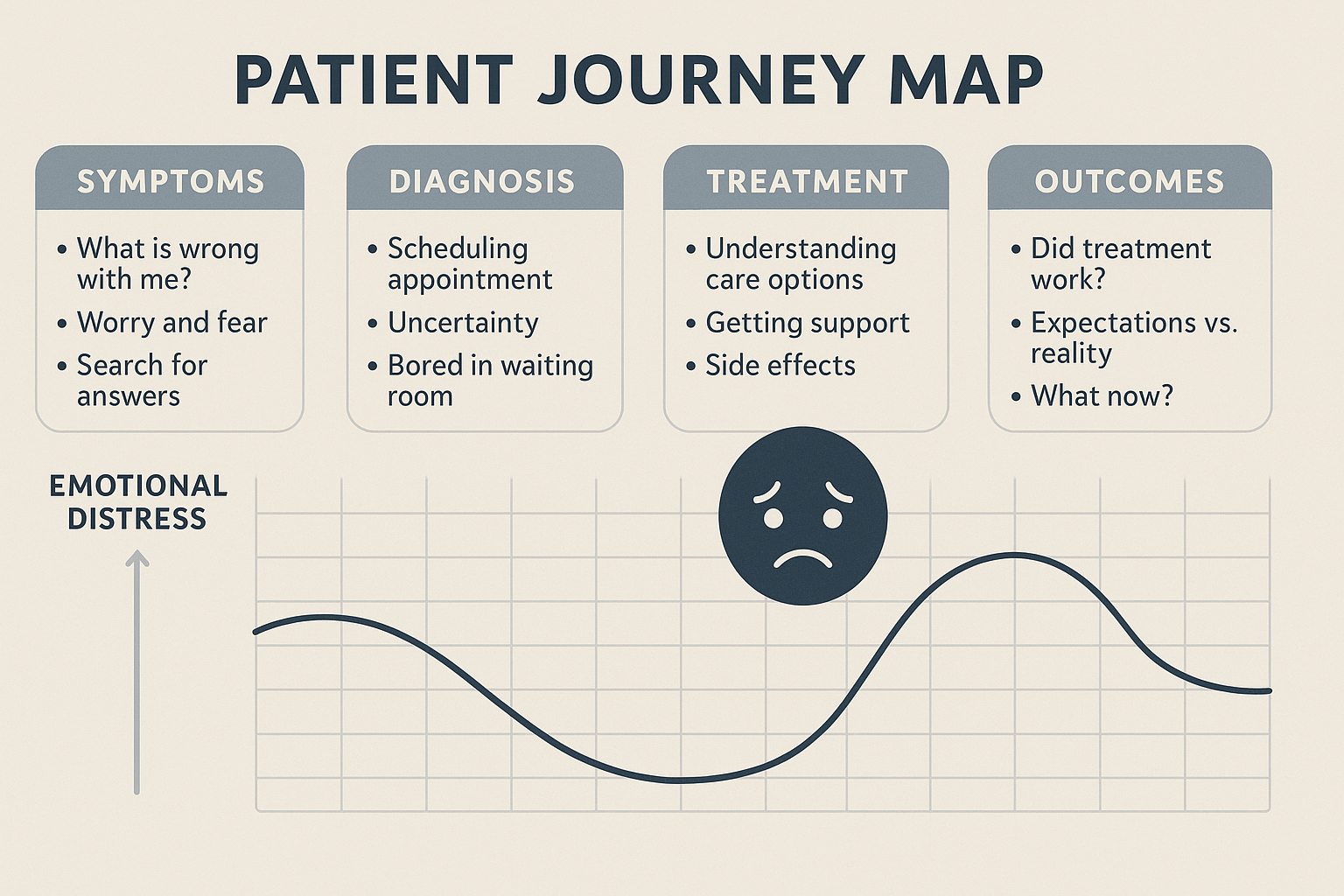

Her emotional arc—fear, anger, and then resolve—never appears on conventional patient journey maps, but it dictated every outcome that followed. How do we account for patient emotions when designing health solutions?

Most teams source patient journeys from health record data or interviews with clinicians. These sources are valuable, but they leave big gaps. Electronic health records hold detailed codes for scans, drugs, and lab values, yet few systems capture social or emotional context. Important drivers and blockers, such as fear of a procedure, worry about job loss, or family stress, are absent. What they do record, endlessly, is medication orders. Unsurprisingly, teams optimise for what they can see, not what patients feel.

Even when data sources accommodate patient emotions, it’s still a challenge to collect sensitive information in situ. By their very nature, emotions are hard to express in the moment. When worry or confusion keeps a patient from sharing a key detail, even the best AI tool will still produce the wrong answer.

Most patient journey slide decks indicate emotions with a single sad‑face where “patient feels concern.” That icon implies a discrete moment; emotions are rarely so simple. Fear peaks when the letter with scan results never arrives, not on the actual “diagnosis day.” Shame surfaces when side‑effects keep the patient away from their daily jobs and careers, not during the clinic consultation. By simplifying real-life emotional impact to emojis and dots on journey map, we end up designing patient brochures, clinical trials and treatment support programs for a world that doesn’t exist.

Elizabeth’s story teaches us two things. First, deep emotions come only from the patient’s own words, often in retrospect and from patients who have gone through the experience; no code or chart field will reveal them. Second, those emotions can change life‑and‑death decisions. If her initial fear had turned into a question instead of silence, the aneurysm might have been clipped years earlier. For a company designing a diagnostic, a therapy, or a support service, missing that moment can mean missed enrolment, late detection, or a failed launch.

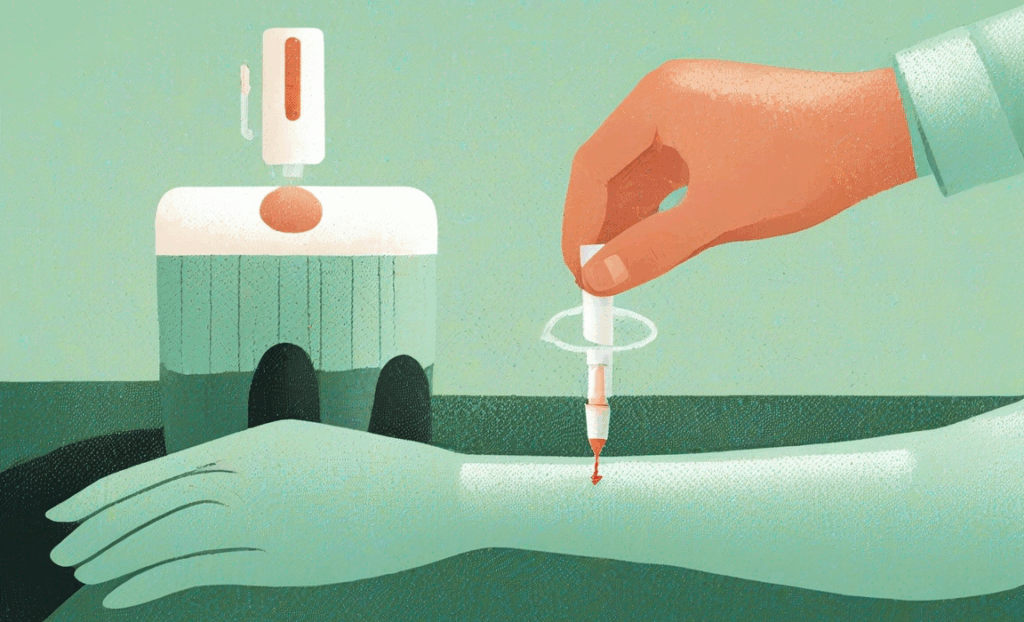

When I wanted to illustrate this point in another therapy area, a colleague mentioned an example with patients who have atopic dermatitis. She told me how potential trial volunteers would pause when they heard the words “punch biopsy.” They imagined all sorts of things: an extremely painful experience, a hole in the skin that never heals, and above all lack of understanding of why this would be necessary. The issue was not the procedure itself; it was the frightening picture in the patient’s mind. Until that picture is addressed and discussed, recruitment can stall. This anxiety would never appear in an EHR and might not surface in a doctor‑focused journey map, yet it can make patients reconsider taking part in the study or dropping off when learning about the protocol.

Volunteers imagine a hole that never heals; afterwards they see a brief pinch that could unlock life-changing data.

True emotional data start with listening sessions, diaries, or moderated online groups with patients that bring real-life, lived experiences. Ideally, you ask patients who have direct experiences with the treatments or diagnostics you are investigating.

I like to plot patient emotions as a layer in the patient journey, aligned to the clinical or treatment journey. You can plot the patient quotes on a simple curve: –5 means panic, +5 means confidence. You soon see deep valleys—waiting for scan results, imagining a biopsy, fearing a job review when eczema flares. Those valleys mark where we must act.

A rich patient journey will be full of relevant stories, sourced directly from patients themselves. Emotions, as we all know, are complicated and will vary between individuals, but with enough voices, clear patterns and commonalities start to emerge. I leave it up to you to determine how far you want to go with emotional mapping, but with just a handful of experienced patients, especially those who have gone through the journey themselves and can walk in the shoes of other patients, you will already start to see the tapestry of patient emotions and the relevance as driver or barrier for your therapy, study, or diagnostic.

Elizabeth’s story shows us the price of a flat patient journey map; layer in patient feelings and you start to position your innovation for real human-centered health care.

Listen to Elizabeth’s full story on the Merakoi Voices podcast: How a Missed Aneurysm Changed My Fight

About Merakoi

At Merakoi, we believe the best healthcare solutions come from those who live with the conditions every day—patients. We connect life sciences companies with patient experts to co-design better treatments, trials, and innovative approaches. Want insights that genuinely matter? Let's chat!

✕